Last week, STAT News asked if I would write something about the FDA’s definition of “Healthy” for them. I agreed because I was planning a blog post on it anyway (posted here).

I wrote a draft and had a great time working with a STAT editor, Patrick Skerritt, to fill in some missing pieces. Here’s how it came out (with a couple of after-the-fact embellishments).

The FDA has announced the set of rules it proposes to enforce for manufacturers to claim that a food product is “healthy.” The proposed rules are a lot better than the labeling anarchy that currently exists. But here’s my bottom line: health claims are not about health. They are about selling food products.

The FDA says that a “healthy” product must meet two requirements: It must contain a meaningful amount of food, and it must not contain more than certain upper limits for saturated fat, sodium, and added sugars.

To illustrate the “healthy” claim, the FDA is also researching a symbol that food makers can use, and might be testing examples like these.

[Source: https://www.regulations.gov/document/FDA-2021-N-0336-0003]

[Source: https://www.regulations.gov/document/FDA-2021-N-0336-0003]

Doing all this, the FDA says, would align “healthy” with the 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and with the Nutrition Facts label that is printed on food packages.

This action is the latest in the FDA’s attempts to simplify food label information so it’s easier for consumers to identify healthier food choices. It is also an attempt to head off what food companies most definitely do not want: warning labels like those used in Chile, Brazil, and several other countries. These have been shown to discourage purchases of ultra-processed “junk” foods, just as they were supposed to, a message understood even by children or adults who cannot read. No wonder food manufacturers will do anything to prevent their use.

If we must have health claims on food packages, the FDA’s proposals are pretty good. They require any product labeled “healthy” to contain some real food (as opposed to a collection of chemical ingredients or, as author Michael Pollan calls them, “food-like objects”), and for the first time they include limits on sugars.

Here’s an example given by the FDA: To qualify for the “healthy” claim, a breakfast cereal serving would need to contain at least three-quarters of an ounce of whole grains and could contain no more than one gram of saturated fat, 230 milligrams of sodium and 2.5 grams of added sugars.

These proposed rules would exclude almost all cereals marketed to children.

But do Americans really need health claims on food products? You might think that any relatively unprocessed food from a plant or animal ought to qualify as healthy without needing FDA approval, and you would be right. But health claims aren’t about health. They are meant to get people to buy food products, not real foods like fruit, vegetables, grains, nuts, meat, poultry, dairy, eggs, or fish.

Food companies love the term “healthy” because it gets people to buy food products.

The history of “healthy”

How did we get to where the FDA needs to require a product to contain real food to be considered “healthy”? Blame KIND bars.

In 2015, KIND (then a small private company, but now owned by Mars) advertised its bars as healthy because they contained whole foods like grains and nuts. But nuts have more fat than the FDA allowed at the time for products to be labeled as “healthy.” The FDA warned KIND that its bars violated the rules for health claims.

KIND fought back. It filed a citizens’ petition arguing that even though nuts are higher in fat than the FDA allowed, they are healthy. The FDA could hardly argue otherwise — of course nuts are healthy — and it backed off. It permitted KIND to use the term and said it would revisit its long-standing definition of “healthy.” That was good news for KIND.

At the time, the FDA’s definition of “healthy” set upper limits for fat, saturated fat, sodium, and cholesterol; required at least minimal amounts of one or more vitamins or minerals; and said nothing about sugars. So the new FDA proposals break new ground in simplifying the nutritional criteria and in putting a limit on sugars.

Front-of-package symbols

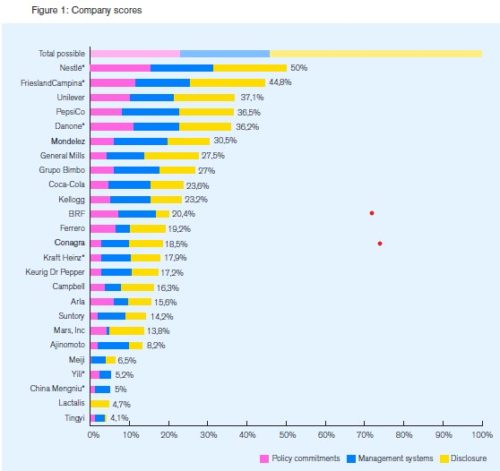

These, too, have a long history with the FDA. In the early 1990s, when the agency was writing the rules for Nutrition Facts labels on food products, it tested public understanding of several prototype designs. As it happened, nobody could understand any of the samples very well, so the FDA picked the one that was the least poorly understood. Soon afterward, food companies and health organizations developed symbols that would allow buyers to recognize at a glance which products were supposed to be good for them.

By 2010, more than 20 such symbols were on food packages. The FDA commissioned the Institute of Medicine to do studies of front-of-package labeling. The Institute’s first report on the subject examined the strengths and weaknesses of all of the symbols cluttering up the labels of processed foods, and recommended that the FDA develop a single symbol that would cover just calories, saturated fat, trans fat, and sodium. Why not sugars too? The Institute said calories took care of them.

But the Institute’s second report did include sugars. It recommended a front-of-package labeling system that would give food products zero, one, two, or three stars (or check marks) depending on how little they had of the undesirable nutrients.

This idea so alarmed food manufacturers that they quickly developed the Facts Up Front labeling system in use today.

This, in my view, is so obfuscating that nobody pays any attention to it. But this scheme, coupled with industry pushback, was all it took to get the FDA to drop the entire idea of a symbol that would tell people what not to eat.

Here we are a decade later with the FDA’s current proposal. This plan is strong enough to exclude huge swaths of supermarket products from self-identifying as “healthy.” Products bearing the “healthy” symbol will have to contain real food and be low in saturated fat, salt, and sugar, as called for by federal dietary guidelines.

The new rules won’t stop “healthy” products from being loaded with additives and artificial sweeteners. And the FDA won’t require warning labels for unhealthy products, which work better than other symbols. But these proposals are a marked improvement over the current situation.

And the FDA might do more. It could look into the idea of warning labels. It already promises to make a decision about the other ambiguous marketing term, “natural.” A decision on that one can’t come soon enough.

As for “healthy,” the FDA is seeking feedback on its proposals. Instructions for filing comments, which can be made until Dec. 28, 2022, are at Food Labeling: Nutrient Content Claims; Definition of Term “Healthy.”

I can’t wait to see what companies wanting to sell ultra-processed food products as “healthy” will have to say about this.

Marion Nestle is professor emerita of nutrition, food studies, and public health at New York University, author of the Food Politics blog, and author of the new memoir, “Slow Cooked: An Unexpected Life in Food Politics” (University of California Press, October 2022).

***********

For 30% off, go to www.ucpress.edu/9780520384156. Use code 21W2240 at checkout.

[Source:

[Source: