The cucumber outbreak: a CAFO problem?

By the time the FDA posted this outbreak alert, the cucumbers had all been picked, shipped, and done their damage.

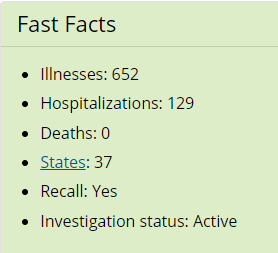

The outbreak

Total Illnesses: 449

Hospitalizations: 125

Deaths: 0

Last Illness Onset: June 4, 2024

States with Cases: AL, AR, CT, DE, DC, FL, GA, IL, IN, IA, KY, ME, MD, MA, MI, MN, MO, NV, NJ, NY, NC, OH, OK, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, VT, WA, WI [31 states]

The CDC investigation: Of 188 people interviewed (69%) reported eating cucumbers.

The product

cucumbers distributed by Fresh Start Produce Sales, Inc. and grown by Bedner Growers, Inc., of Boynton Beach, FL. Recalled cucumbers are beyond shelf life and should no longer be available for sale to consumers in stores. Bedner Growers, Inc.’s growing and harvesting seasons are over. There is no product from this farm on the market and likely no ongoing risk to the public.

The self-protective reaction

According to Food Safety News,

the Florida Department of Agriculture (FDOA) called the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) tracing of a Salmonella outbreak to a local cucumber grower “at best inaccurate, and at worst misleading.” Apparently, the head of food safety at the FDOA, who told the FDA in an email “We find the science inaccurate, unsubstantiated and unnecessarily damaging to the firm implicated.”

Comment

This outbreak is worth special attention, not least because so many people were affected in so many states, and the cucumbers were gone by the time investigators knew they were the most likely cause.

- Half the cases were due to a new kind of Salmonella, S. Braenderup.

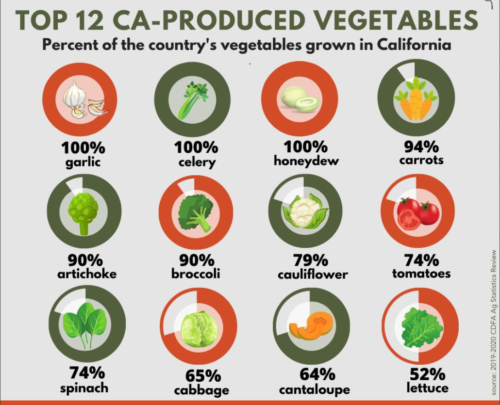

- The FDA idenified S. Braenderup in untreated canal water used for irrigation.

Salmonella in the water? This means there must be some kind of enormous CAFO (Confined Animal Feeding Operation) nearby, spilling its cattle, dairy, or poutry waste into local streams.

The regulatory issues

This brings me to law professor Timothy Lytton’s latest paper on precisely this issue: Lytton, Timothy D., Known Unknowns: Unmeasurable Hazards and the Limits of Risk Regulation (July 02, 2024). Oklahoma Law Review, Vol. 76, No. 4, p. 857, 2024.

This Article develops general principles for addressing known unknowns using a case study of efforts to regulate agricultural water quality. Contaminated water used to cultivate fresh produce is a well-known cause of recurrent foodborne illness outbreaks. Unfortunately, it has, so far, proven impossible to reliably quantify the risk of human illness from any given source of agricultural water.

At least one problem here is the split in regulatory authority between FDA (cucumbers) and USDA (animals). FDA has no authority over CAFOs. Its authority stops at the farm. How is the cucumber farmer supposed to stop toxic forms of Salmonella from getting onto cucumber fields?

That is the insoluble regulatory problem Lytton’s piece addresses.